Simply put, GLEAM® is UnboundEd’s blueprint for effective instruction — instruction that is grade-level, engaging, affirming, and meaningful. Instruction that ensures every student in every classroom gets what they need to succeed academically and throughout their lives and careers. Instruction that equips educators everywhere to break the predictability of historic achievement patterns so all kids thrive.

GLEAM Instruction is at the heart of everything we do. UnboundEd exists to support educators at every level in providing their students with grade-level, engaging, affirming, and meaningful instruction.

The principles of GLEAM Instruction are deeply rooted in evidence-informed practices, building on insights from exceptional educators, learning science, and student-centered teaching methods.

When we say grade-level, engaging, affirming, and meaningful, we mean:

GRADE-LEVEL: Instruction that is aligned with the grade-appropriate college and career standards.

ENGAGING: Instruction that fosters persistence, active learning, and academic agency by tapping into students’ assets.

AFFIRMING: Instruction that builds a caring, collaborative classroom community by uplifting students’ identities and experiences in service of learning.

MEANINGFUL: Instruction that cultivates civic agency and critical thinking by making learning relevant to issues students encounter beyond the classroom.

This blog series, comprised of three posts, delves into GLEAM instruction and how it can create more effective learning experiences for all students.

Grounded in Grade-level

The explicit descriptions of college and career readiness in the standards and the evidence-based focus on what matters most for learning are crucial. As TNTP’s landmark study, The Opportunity Myth, demonstrated, students meet our expectations and thrive when we provide them with instruction aligned to grade-level standards. Educators who don’t use instruction and lessons aligned to grade-level standards begin with low expectations, which students sink to meet.

But grade-level rigor and standards-aligned curriculum aren’t enough. To solidify the impact of grade-level instruction, teaching needs to be engaging, affirming, and meaningful.

Engaging instruction builds students’ interests tied to their knowledge and culture, helping them see themselves as learners with agency. Teachers who enact engaging instruction have an awareness of and accountability for the curriculum’s demands for rigor and productive struggle. These teachers use students’ academic and linguistic backgrounds and local context as on-ramps to learning in ways that extend students’ “intellective capacity” (Hammond, 2015), the ability to process complex information effectively and with increasing independence.

Affirming instruction honors all students and their varied experiences and backgrounds in the context of grade-level learning, creating a space where students feel safe, supported, and immersed in their learning. Teachers who provide affirming instruction articulate or demonstrate how students can use the learning in their world and the larger world. These teachers see, value, and affirm students’ full humanity and all of their backgrounds.

Meaningful instruction connects learning beyond the classroom by cultivating civic agency and informed critical engagement with current and historical norms, stories, and ideas. Teachers who provide meaningful instruction find room in the curriculum to develop students’ critical thinking through dialogue, debate, questioning, and writing. These teachers build their own deep content knowledge and develop a lens focused on their students’ realities.

More than Technical Actions and Skills

There is no recipe for GLEAM instruction. It is not a rubric nor a list of indisputable actions teachers take in the classroom. Importantly, GLEAM instruction is more than a set of technical skills.

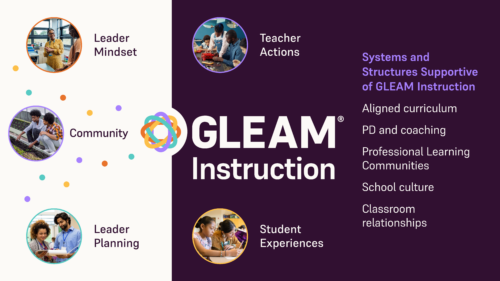

Certainly, understanding “what to do” is essential, but it is not enough. That’s why our GLEAM hypothesis goes further. Only when teacher mindset and teacher planning, along with evidence-informed, aligned curriculum, are put in service of grade-level, engaging, affirming, and meaningful instruction, do we see the teacher actions and student experiences that exemplify the curiosity, creativity, and critical thinking of impactful education.

Outside of the Classroom

Let’s unpack the elements of our hypothesis a bit. We believe that how educators think and spend their time outside the classroom matters, especially teacher mindsets and planning. Teachers making GLEAM a reality know grade-level academic standards, are open to growing understanding of their students’ backgrounds, and believe that students can meet grade-level expectations through relevant content and multiple ways of demonstrating knowledge.

Educators bring these mindsets to bear during their instructional planning when they do things like:

- Commit to understanding their students’ personal and academic identities and the rich knowledge they bring to the classroom.

- Reflect continuously on students’ backgrounds and their impact on instruction and student relationships.

- Continuously sharpen their knowledge of content and pedagogy.

Who educators are and what they do outside of the classroom significantly influence how they teach; these mindsets and planning practices are critical for GLEAM instruction to occur.

GLEAM can bring effective instruction and grade-level learning to life and create opportunities for students to feel seen, heard, and valued, thereby deepening their investment in their academic success.

Reference

Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin Press.

Read the blog series